Severan dynasty

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Severan dynasty | ||

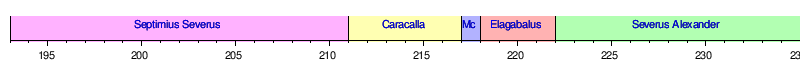

| Chronology | ||

|

193–211 |

||

|

with Caracalla 198–211 |

||

|

with Geta 209–211 |

||

|

211–217 |

||

|

211 |

||

|

Macrinus' usurpation 217–218 |

||

|

with Diadumenian 218 |

||

|

218–222 |

||

|

222–235 |

||

| Dynasty | ||

| Severan dynasty family tree | ||

|

All biographies |

||

| Succession | ||

|

||

The Severan dynasty, sometimes called the Septimian dynasty, ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235[1]: 1292 . It was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211)[1]: 1351 and Julia Domna, his wife, when Septimius emerged victorious from civil war of 193 - 197, which begun with the Year of the Five Emperors. Their two sons, Caracalla (r. 192–217)[1]: 211 and Geta (r. 211)[1]: 1350 , ruled briefly after the death of Septimius. In 217 - 218 there was a short interruption of dynasty's control over the empire by reigns of Macrinus (r. 217–218)[1]: 1292 and his son Diadumenian (r. 218) before Julia Domna's relatives assumed power by raising her two grandnephers, Elagabalus (r. 218–222)[1]: 212 and Severus Alexander (r. 222–235)[1]: 212 , in succession to the imperial office[1]: 1292 .

The dynasty's women, Julia Domna, the mother of Caracalla and Geta, and her sister, Julia Maesa, the mother of Julia Soaemias and Julia Mamaea, mothers of Elagabalus and Severus Alexander respectively, were all powerful augustae. They were also instrumental in securing imperial positions for their male relatives.

Although Septimius Severus restored peace following the upheaval of the late 2nd century, the dynasty's rule was disturbed by unstable family relationships and political instability, especially the rising power of the praetorian prefects[2]: 170 . All this foreshadowed the Crisis of the Third Century[3]: 195 .

History

[edit]

Septimius Severus (193–211)

[edit]

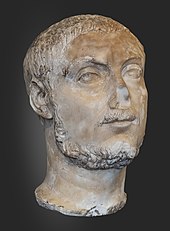

In April 9 145, Lucius Septimius Severus was born in Leptis Magna[3]: 1 , then in the Roman province of Africa Proconsularis and now in Libya, into a Libyan-punic family of equestrian rank[4]: 2-3 [5]. He rose through military service to consular rank under the later emperors of the Antonine dynasty[citation needed]. In summer 187 he married a Syrian noblewoman Julia Domna and the marriage produced two boys: Caracalla and Geta. Julia Domna also held a prominent political role in government during her husband's reign[citation needed]. Severus was proclaimed emperor in 193 by his legionaries in Noricum[4]: 3 during the political unrest that followed the death of Commodus[3]: 97 , and secured sole rule over the empire in early 197, after defeating Clodius Albinus at the Battle of Lugdunum[3]: 125 [4]: 6 .

In late 197 Severus fought a successful war against the Parthians[3]: 130 [4]: 6 , between 208 and 210 he campaigned with success against barbarian incursions in Roman Britain[3]: 180 and rebuilt Hadrian's Wall[citation needed]. In Rome, his relations with the Senate were poor, but he was popular with the commoners and with his soldiers, whose salary he raised. Starting in 197, his praetorian prefect, Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, was growing in influence, but he would be executed in 205. Septimius died, from natural causes, in early 211 while on campaign in Britain[3]: 187 [4]: 8 .

During his reign, Severus debased the Roman currency several times -- for example upon his accession he decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 81.5% to 78.5%[6]. The Jews experienced more favorable conditions under the Severan dynasty: According to Jerome, both Septimius Severus and Antoninus "very greatly cherished the Jews."[3]: 135

Septimius was succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta, whom he had elevated as co-emperors in the years preceding his death[1]: 211 [4]: 15 . The growing hostility between the brothers was initially buffered by Julia Domna's mediation[4]: 15-6 .

Caracalla (198–217)

[edit]

The eldest son of Severus, born in 188 as Lucius Septimius Bassianus[1]: 211 [4]: 6 . "Caracalla" was a nickname referring to the Gallic hooded tunic that he habitually wore[4]: 18 . In 195 Severus made him caesar and renamed him to Aurelius Antonius Marcus after Marcus Aurelius[1]: 211 [4]: 5 . A while later, in 198, Severus made him augustus[1]: 211 [4]: 7 while also naming Caracalla's younger brother, Geta, to caesar[1]: 1350 [4]: 7 .

Caracalla hated his brother, and conflict between them culminated in the assassination of the latter in 211[1]: 211 [4]: 15 . After the murder of his brother, Caracalla tried and gained goodwill of his legionaries with lavish pay raises[1]: 211 [4]: 16 . However, he also purged many of Geta's supporters[4]: 16 .

During his campaigns Caracalla let her mother, who accompanied her son, to handle many official matters by correspondence and refer to him only major issues[4]: 17 . In 213 he campaigned against the Alamanni, and in 214 he fought with the Danubian Carpi[1]: 212 . Later he raised a Macedonian phalanx to emulate Alexander the Great, and marched through Asia and Syria to Alexandria, inviting mockery of many whom he executed[1]: 212 . During his reign he bestowed, for reasons not entirely clear, Roman citizenship to all non-slaves living within the borders of the empire[4]: 17 . The Baths of Caracalla in Rome are the most enduring monument of his rule[citation needed].

Caracalla died in April 8 217[1]: 211 [4]: 19 . He was murdered near Carrhae while en route to a campaign against the Partians[1]: 212 , the murder being committed by an evocatus attached to the Praetorian Guard on the order of a preatorian prefect, the future emperor Macrinus[4]: 19 .

Geta (209–211)

[edit]

The younger of Severus' two sons, Geta, was born in 189[4]: 6 . He was made caesar in 198 and co-augustus in 209[4]: 8 or 210[1]: 1350 alongside his father and older brother Caracalla[1]: 1350 . Unlike the much more successful joint reign of Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180) and his brother Lucius Verus (r. 161–169) the previous century, relations were hostile between the two Severan brothers[1]: 211 , and soon after their father's death Geta was murdered by his brother Caracalla[1]: 1350 . Geta was murdered in their mother's apartments, and died clung to his mother, by order of Caracalla[4]: 16 , who then ruled as sole emperor.

Interlude: Macrinus (217–218)

[edit]Macrinus was the first Roman emperor who did not come from a senatorial family[1]: 1039 . He was born in 164 at Caesarea in Mauretania, now Cherchell, Algeria[citation needed]. Though not related to Severans while also being of just equestrian rank and having been born into a Moorish family[4]: 20 [1]: 1039 , he rose through the ranks all the way to being a praetorian prefect under Caracalla[1]: 1039 . In 217 Macrinus became involved in a successful conspiracy to kill Caracalla[1]: 1039 , and soon after the murder trooops saluted Macrinus as augustus[8]: 10 [1]: 1039 .

His made peace with the Parthian Empire[1]: 1039 , which involved paying reparations for the damage caused by Caracalla's campaigns[8]: 10 [4]: 20 . His troops considered the terms degrading to the Romans[8]: 10 . One of the reasons for his eventual downfall was his attempt at saving by paying serving soldiers of the Eastern troops by higher pay scales established during the rule of Caracalla while paying the new recruits by lower pay scales from the time of Septimius[4]: 20 [8]: 10 [1]: 1039 -- his troops were not impressed[4]: 20 . Due to a continuing threat from Parthia, he kept the rebellious forces in Syria[4]: 20 , where they became one way or the other acquainted with Elagabalus[8]: 11 .

In May 218 troops camping near Elesa revolted and hailed Elegabalus as emperor[4]: 21 [8]: 12 . After months of rebellion and a failed attack on the rebellious troops, Macrinus met the army of Elagabalus near Antioch where he was decisively defeated[4]: 21 [8]: 14 [1]: 1039 . Macrinus managed to escape with his son to Chalcedon where he was apprehended to be taken back to Antioch, but the guards murdered him en route[4]: 21 . During his rule Macrinus never entered the city of Rome[8]: 10 .

Elagabalus (218–222)

[edit]

Elagabalus was born Varius Avitus Bassianus in 203[1]: 212 and became known later as Marcus Aurelius Antonius[1]: 212 . The name "Elagabalus" followed the Latin nomenclature for the Syrian sun god Elagabal, of whom he was a priest[8]: 11 . At the age of 14, in 218, Elagabalus was crowned emperor by Gallic Third Legion[8]: 9 [1]: 212 .

There are two different versions how Elagabalus gained the throne. In one version of events, Elagabalus's grandmother, Julia Maesa, Julia Domna's sister and sister-in-law of Septimius Severus, persuaded the Legio III Gallica to rebel against Macrinus[1]: 212 by claiming that Elagabalus was actually Caracalla's bastard son with one of her daughters[8]: 11 . She also used her enormous wealth to get soldiers swear fealty to Elagabalus[10]. Having succeeded, Maesa and her family were invited to enter the camp, where Elagabalus was clad in imperial purple and crowned as emperor[8]: 11 . Another account of the events tells how Elagabalus was being protected and raised by Gannys, a foster father and lover of his mother, Julia Soaemias[8]: 11 . In this version of events, Gannys dressed young Elagabalus in Caracalla's childhood clothes and smuggled him into the camp at night, where soldiers eventually revolted the next morning[8]: 11 . In any case, he did arrive as emperor in Rome by summer 219[8]: 18 [1]: 212 .

Historical sources treat his reign negatively[8]: 21 , but many of his failures can not be affirmed. However, epigraphical and numismatic evidence shows that Elagabalus did replace Jupiter with Elagabal in late 220[8]: 18 , and he also married a Vestal Virgin called Aquilia Severa[1]: 212 . In addition to these offences to Roman sensibilities, he was also accused of being murderous and bloodthirsty, but executions during his reign appear to be politically motivated instead of being the result of simple bloodlust[8]: 97 . Many, if not all, stories about his effeminacy, extravagance, and licentiousness are imaginations of ancient authors[8]: 122 .

In 221, seeing that her grandson's outrageous behaviour could mean the loss of power, Julia Maesa persuaded or forced Elagabalus to adopt his cousin, Severus Alexander[1]: 212 , as caesar and his heir[8]: 37 . At the same time he was forced divorce Aquilia in order to marry Annia Faustina, a relative of Marcus Aurelius, only to take Aquila back in a few months before the end of 221[1]: 212 . Elagabalus also tried on several occasions to murder Alexander, which enraged the troops[8]: 40 [1]: 212 . In 222 Elagabalus was murdered and his corpse thrown into the sewer[8]: 42 . The next day his cousin Alexander was hailed emperor by the troops[8]: 41-2 .

Alexander Severus (222–235)

[edit]

Born Gessius Bassianus Alexianus in ca. 209[1]: 212 , in 221 Alexander was adopted at by Elagabalus from whence he was called Marcus Aurelius Alexander Caesar[1]: 2121 . The adoption happened at the urging of Julia Maesa[1]: 212 , who was the grandmother of both cousins.

His cousin Elagabalus had made several attempts at Alexander's life, which prompted the troops to mutiny, and things came to a head on March 6 when Elagabalus was put to death and Alexander raised to the throne[4]: 22 [8]: 40-2 .

Ruling from the age of 14 under the influence of his mother[1]: 212 , Julia Avita Mamaea, ancient writers presented his reign as an efficient regime like the rule of Septimius Severus[4]: 22 . The rising strength of the Sasanian Empire (r. 226–651) heralded perhaps the greatest external challenge that Rome faced in the 3rd century; however, in 231 Alexander organised an expedition to Parthia, nominally leading it, and by this did maintain control over the province of Mesopotamia[1]: 212 .

Alexander's reign ended in early 235 when he was murdered, together with his mother, by his own troops while he was wintering in Germany where he was in order to prosecute a war in Upper Germania[1]: 213 . He was deified in 238 after his memory had been condemned for a few years[1]: 213 .

The death of Alexander was the epochal event beginning the troubled Crisis of the Third Century[8]: 89 . His successor was Maximinus Thrax (r. 235–238), the first in a series of weak emperors, which ended 50 years later with the Tetrarchy instituted in the reign of Diocletian (r. 284–305).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au

Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Scott, Andrew (May 2008). Change and discontinuity within the Severan dynasty: the case of Macrinus (PhD thesis). New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anthony R.Birley (1988). Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. Taylor & Francis e-Library. ISBN 0-203-02859-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Bowman, Alan; Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter, eds. (2008). Volume 12: The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. The Cambridge Ancient History (2 ed.). ISBN 9781139053921.

- ^ Gall, Joël Le; Glay, Marcel Le (1992). "Chapitre III - Septime Sévère ou la « revanche d'Hannibal »". Peuples et Civilisations: 541–577. ISBN 978-2-13-044280-6.

- ^ "Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"". Archived from the original on 10 February 2001. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part I, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Icks, Martijn (2013). The Crimes of Elagabalus: The Life and Legacy of Rome's Decadent Boy Emperor. I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 9781780765501.

- ^ Mattingly & Sydenham, Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. IV, part II, p. 43.

- ^ "The Severan Women". Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Benario, Herbert W. 1958. "Rome of the Severi." Latomus 17:712–722.

- Birley, Eric. 1969. "Septimius Severus and the Roman Army." Epigraphische Studien 8:63–82.

- De Blois, Lukas. 2003. "The Perception of Roman Imperial Authority in Herodian’s Work." In The Representation and Perception of Roman Imperial Power. Edited by Lukas De Blois, Paul Erdkamp, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, and S. Mols, 148–156. Amsterdam: J. C. Gieben.

- De Sena, Eric C., ed. 2013. The Roman Empire During the Severan Dynasty: Case Studies in History, Art, Architecture, Economy and Literature. American Journal of Ancient History 6–8. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias.

- Markus Handy, Die Severer und das Heer, Berlin, Verlag Antike, 2009 (Studien zur Alten Geschichte, 10).

- Langford, Julie. 2013. Maternal Megalomania: Julia Domna and the Imperial Politics of Motherhood. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Moscovich, M. James. 2004. "Cassius Dio’s Palace Sources for the Reign of Septimius Severus." Historia 53.3: 356–368.

- Simon Swain, Stephen Harrison and Jas Elsner (editors), Severan culture, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Ward-Perkins, John Bryan. 1993. The Severan Buildings of Lepcis Magna: An Architectural Survey. London: Society for Libyan Studies.